This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

Lauren Williams took a job with Paper, one of the biggest virtual tutoring companies used by U.S. schools, because she wanted to help kids.

Williams, a self-described English and history buff who lives just south of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, liked the work at first. As she helped students with their writing, it felt like students were getting personal attention they badly needed.

But as Paper ratcheted up the pace and volume of her tutoring assignments last year, Williams grew alarmed.

By this spring, she was routinely working with five students at once on the company’s online platform, which resembles a text-based instant messenger. She found herself toggling between kindergarteners learning to read and high-schoolers writing college essays, frantically trying to respond to each student’s message within Paper’s 50-second time limit.

Her breaking point came as Paper put new pressure on tutors to review essays faster — in part by recycling comments they’d written before.

“I was like: ‘No, I can’t do this,’” said Williams, who quit in March. That kind of help, she concluded, is “not doing what’s right by the kids.”

Tapping into the federal government’s historic investment in helping students recover from the pandemic, Paper has won contracts worth tens of millions of dollars telling schools it offers one-on-one tutoring with subject experts.

But the company often fails to deliver that basic service to students, a Chalkbeat investigation has found. In fact, tutors often juggle multiple students at once — a setup other virtual tutoring companies avoid — sometimes in subjects they don’t know well.

Paper argues that a student’s experience is always one-on-one, since students typically aren’t aware their tutor is working with others.

But the company’s practices and internal messaging suggest top officials know multi-tasking can be a challenge for tutors. It has even paid tutors “surge” bonuses of two to three times their normal pay rate for every minute they work with four or more students at once.

“At least when you’re in that stressful experience of having four kids in your classroom you know that you’re making double pay,” said Julia Drury, Paper’s senior director of operations, at a virtual company meeting last summer. “If you’re doing the work of two tutors, then you should be paid for the work of two tutors.”

School districts and state education agencies, meanwhile, are investing millions of COVID relief dollars in Paper’s services, sometimes none the wiser.

To report this story, Chalkbeat interviewed more than a dozen current and former Paper employees and reviewed hundreds of pages of company documents, including screenshots of internal conversations among employees.

In an interview, Paper’s CEO, Philip Cutler, did not dispute Chalkbeat’s findings that tutors are often working with more than one student at a time and that tutors sometimes work with students on unfamiliar subjects.

But he maintains that Paper is delivering one-on-one tutoring because tutors who work with multiple students do so in separate, individual sessions.

“The student’s experience is one-on-one,” Cutler told Chalkbeat in June. “The tutor can be supporting multiple people. The idea is that the attention I’m getting is dedicated to me.”

Several school officials said they were not aware that Paper tutors were often working with multiple students at once until Chalkbeat told them.

“The department will follow up with Paper about this and continue to monitor, throughout the upcoming school year, if this practice has any impact on student engagement and/or satisfaction of services,” wrote Jean Cook, a spokesperson for the Mississippi Department of Education, one of Paper’s largest clients, in an email to Chalkbeat.

Paper tutors juggle multiple students at once

As students fell behind during the pandemic, many researchers and education officials encouraged schools to tutor their students. That recommendation was backed by years of research that has found tutoring can deliver positive academic results, especially when kids get one-on-one help.

Amid staffing shortages, many school districts struggled to find and hire in-person tutors. That’s why many schools were drawn to Paper, which relies on 2,000 mostly part-time tutors who typically log on virtually from their homes across the U.S. and Canada.

Today the nine-year-old, Montreal-based company holds contracts worth tens of millions of dollars to tutor more than three million students in 600 districts across the U.S. and Canada. Much of that is backed by federal COVID relief money.

Chalkbeat previously found that Paper’s tutoring often goes unused, particularly by students who most need help. The company lost a contract earlier this year with the state of New Mexico, after officials there said Paper had failed to meet students’ needs.

Paper has told potential clients, like New Mexico, that it provides “a 1:1 student-tutor ratio.”

“We tailor instruction for each student,” Paper wrote to New Mexico education officials last fall in a proposal to work with the state. “With our 1:1 support, your students will receive the personalized attention they need.”

But Paper tutors often can’t do that, according to interviews with more than a dozen current and former Paper tutors. The company’s employee handbook tells tutors they should be able to work comfortably with three students at once.

“We’ve found this to usually be manageable without sacrificing quality,” the handbook states. It adds: “there is no maximum number of students a tutor can be matched with simultaneously.”

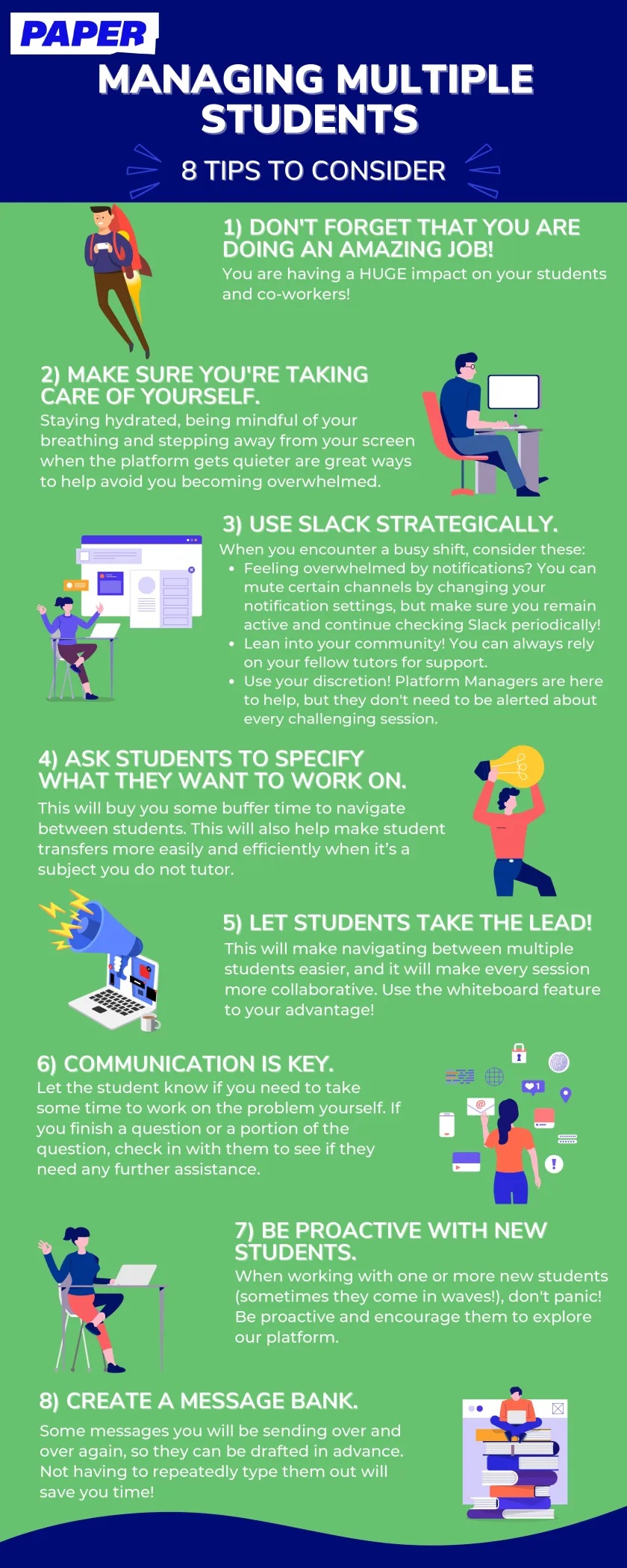

Paper offers tipsheets for tutors meant to help them work with multiple students at once. One guide obtained by Chalkbeat tells tutors to ask students questions about what they want to work on to “buy you some buffer time to navigate between students.” Tutors can also “LET STUDENTS TAKE THE LEAD!” to make it “easier” to toggle between sessions.

Cutler said it’s rare for tutors to work with more than three students at once and that it only happens for short bursts of times, or “surges.”

Paper’s own data, provided to Chalkbeat by the company, shows that tutors spent 33% of their working hours over the last school year helping two students at once, 10% of their time helping three students at once, and just under 2% of their time helping four or more students. The rest of the time, tutors worked with one or no students.

But several tutors said those rates don’t accurately reflect their workload, which spikes in the mornings and afternoons. Internally, Paper has acknowledged that tutors who work in high-demand subjects like math experience surges of four or more students “on kind of an ongoing basis,” as Drury said at the virtual company meeting last summer.

One math and science tutor told Chalkbeat he’d helped a dozen students at once. Another math and science tutor said she’d gotten 10 students during a surge.

“You just keep switching tabs,” the tutor said. “I feel bad for some of these kids who are using the platform.”

Paper has resisted making changes that could cut down on tutor multitasking, such as adding a waiting room or scheduling option, because they could result in fewer students using Paper, according to a former manager who left Paper last year after several years with the company.

“The response to it was just like: ‘We don’t want to turn students away,’” said the former manager, who asked not to be named because they signed a confidentiality agreement with Paper that prohibits sharing details about the company’s internal operations. “The quality of the service was always secondary.”

Cutler said “that’s certainly not the case” and that Paper has been “very focused on delivering a high level of quality over cost.”

This kind of juggling is not the industry standard. Many other virtual tutoring companies offer intentional group sessions where students work together on similar assignments. Others conduct tutoring sessions over live audio or live video, which makes toggling between students nearly impossible. Paper does neither.

And other companies that offer text-based tutoring limit the number of students a tutor has at once.

TutorMe, for example, said its platform allows tutors to conduct only one session at a time. Varsity Tutors said when a student requests an on-demand tutor, a tutor can’t get another student “until the session is resolved.” Tutor.com said the maximum number of students a tutor can have at once is two, and that happens in only 2% of sessions.

“We NEVER work with multiple students in DIFFERENT individual sessions at the same time,” Mike Cohen, the CEO of Cignition, a California-based company that contracts with the Denver, Los Angeles, and Baltimore school districts, wrote in an email to Chalkbeat.

Figuring out how to run a tutoring program that delivers quality help to a significant number of students without breaking the bank remains a huge challenge for schools, especially as COVID relief funds dwindle. One of Paper’s biggest selling points is that districts can offer unlimited virtual tutoring to all their students at a fixed price. If lots of students use it, it can be less expensive than pricey in-person tutoring programs.

Experts say they understand how those competing needs drove some districts to select on-demand homework help, like the kind Paper offers, even though it does not have many of the hallmarks of effective tutoring.

“It’s easy to implement,” said Jennifer Krajewski, who helps schools choose evidence-based tutoring programs through a Johns Hopkins University initiative called ProvenTutoring. “And it doesn’t necessarily require shifts in schedules. Those are real challenges that schools are facing.”

But when districts express interest in virtual, on-demand tutoring, Krajewski said she cautions school leaders to ask about how many students tutors will work with at once, and what kind of relationship students will build with tutors. Several companies, including Paper, match students with a new virtual tutor every time they log on.

“A big part of why tutoring is so powerful is that human connection with somebody who cares about you,” said Amanda Neitzel, a Johns Hopkins assistant research scientist who works with schools through ProvenTutoring. “If you are doing a virtual model with somebody who is juggling two other kids, even in the best-case scenario, how much are you actually doing that?”

Some schools left in dark about Paper’s tutoring practices

Tutors have repeatedly told Paper that they worry the company’s advertising is misleading schools, internal records and interviews show. In March, one tutor asked on Slack, the company’s internal messaging platform, if Paper would stop saying it offers one-on-one tutoring on its website because “it has not been that way, according to many tutors.” A top manager defended the description.

“You are working with a student in an individual session!” Caroline Schwim, Paper’s senior manager of teaching and learning, wrote in response. “We are open with our districts about tutors working with multiple sessions which helps us remain affordable for them!”

Cutler says school districts are informed that tutors may be working with multiple students at once “through the sales process” and that “districts are fine with that.”

But the Mississippi Department of Education, which is paying Paper $10.7 million to tutor up to 350,000 students across the state, told Chalkbeat it did not know. A state official there said the department would talk with Paper about this practice and monitor whether it was affecting student engagement or satisfaction with tutoring.

Clarissa Trejo, a spokesperson for Fontana Unified schools in California, said the district “has never had a conversation regarding how many students a tutor would be helping at a time.” The district, which has paid Paper $1.9 million to tutor some 38,000 students, had no concerns about the quality of Paper’s tutoring, Trejo added.

Meanwhile, officials with Arlington Public Schools in Virginia and Los Angeles Unified told Chalkbeat they didn’t learn that tutors may help multiple students at once until after they had agreed to work with Paper and were putting the program in place. Still, a Los Angeles schools spokesperson said Paper is “an essential component” of the district’s plan for giving students “individualized instruction.”

Other school officials said they were aware before they hired Paper. Clark County schools in Nevada, which is paying Paper nearly $13 million to tutor 302,000 students, said the district found out in its initial conversations with Paper that tutors “may conduct simultaneous one-on-one learning sessions with multiple students.”

The Tennessee Department of Education, which has a contract with Paper worth up to $1.3 million, said its contract permits Paper tutors to work with up to three students at a time — a limit that doesn’t typically appear in other Paper contracts.

“We have received no complaints or evidence that Paper is violating their contract,” wrote Brian Blackley, a spokesperson for the state, in an email.

Paper tells tutors to Google their way through sessions

When students log on to Paper’s platform, they expect to be matched with a tutor who knows something about the subject they need help with. Paper says it employs “experts across K-12 subject areas” on its website, and that it gives tutors aptitude tests to vet their knowledge.

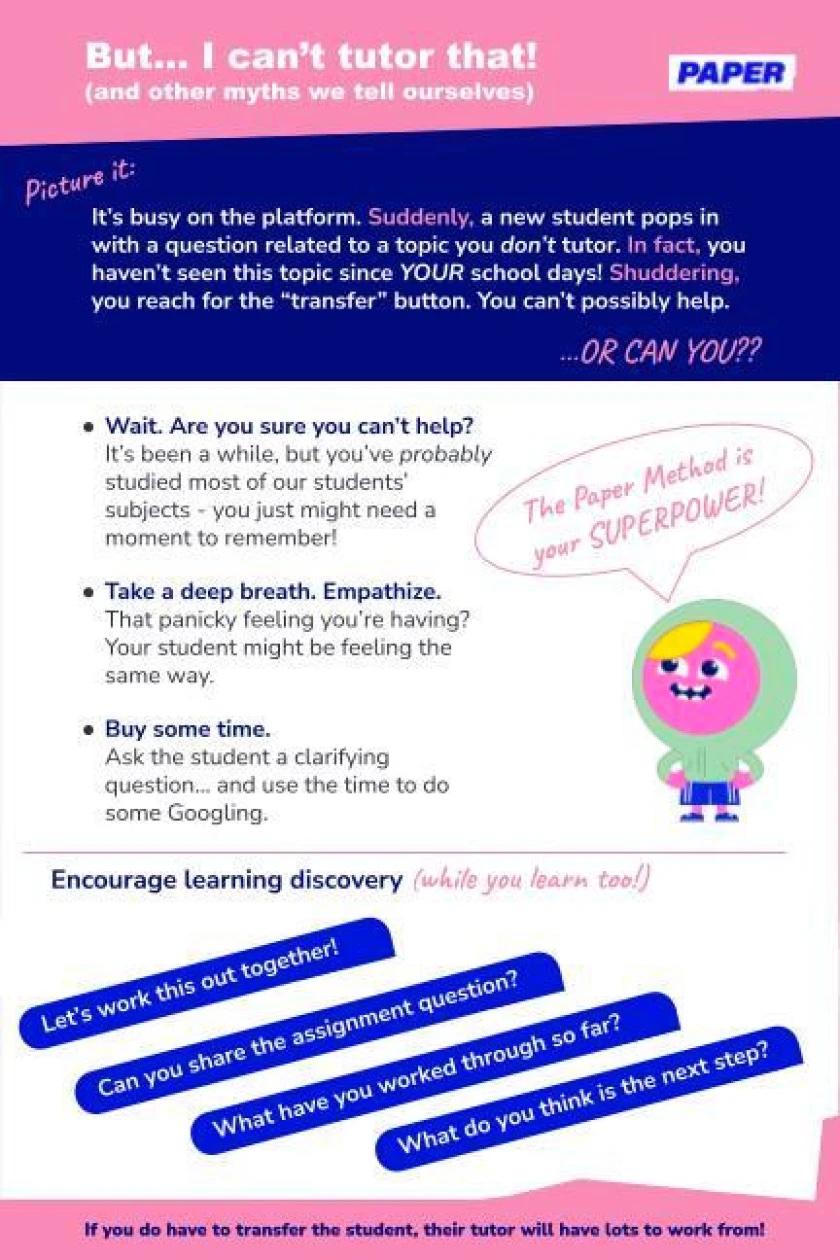

But in practice, several current Paper tutors said they are routinely matched with students who need help with subjects they don’t know. Tutors who feel stuck can transfer a student to a colleague with more expertise, but they can be fired if they do that too often.

Paper has told uncertain tutors to buy time by asking the student a question while they essentially Google their way through the session.

“Even if you’re uncertain, give it a go,” Schwim told tutors last fall during a video training, according to a screenshot viewed by Chalkbeat.

The result looks something like what happened to Shannon Dickinson’s daughter, a high school junior in Las Vegas. Dickinson, a kindergarten teacher, had heard Clark County schools was offering tutoring through Paper, and she urged her daughter to give it a try when she was struggling with her pre-calculus class in January.

But each time the 11th grader logged on and showed a Paper tutor her math problem, she waited for a long time only to find out the tutor couldn’t help.

“It would be like 45 minutes later: ‘Sorry I can’t help you, I’m going to transfer you to someone else,’” Dickinson recalled. “Then she’d have to do the process again.” After several failed attempts to get help, Dickinson’s daughter told her: “This is not worth my time.”

When Chalkbeat told Dickinson that Paper’s tutors are told to Google their way through sessions when they’re stuck, she was stunned.

“Oh geez,” she replied. “Well, high schoolers can do that too!”

Wendi Dunlap, who worked for Paper for just over a year before she quit in March, has seen this play out from the tutor’s side. Earlier this year, Dunlap, an English and history tutor, got paired with a middle schooler with a math question. Dunlap tried to help anyway, following the company’s protocols. But when the student checked the work they’d done against an answer key, she reported back: “That’s completely wrong.”

Dunlap apologized and scrambled to transfer the student to a math tutor, but it was too late. The student had signed off.

“I felt so horrible,” Dunlap said. “It wasn’t fair to her.”

A math and economics tutor who’s been with Paper for four years said she once spent 45 minutes trying to convince her manager over Slack that she needed to transfer a high school student with a chemistry question that she had “zero clue” how to solve. To stall for time, she asked the student for their notes. Essentially, though, the student spent that time “doing nothing,” the tutor said.

“It’s just leading to the student getting more frustrated,” the tutor said. “This is not right.”

Cutler said scenarios like those are uncommon. The guidance Paper has given to tutors, he added, is similar to what teachers are expected to do if a student asks a question the teacher doesn’t know how to answer.

“I don’t dismiss the student, I say: ‘Let’s figure it out,’” Cutler said. “‘Let’s pull up the internet.’”

Paper also puts pressure on tutors to work quickly. Tutors are expected to respond to students within 50 seconds, internal records show, regardless of how many students they have at once or how complicated the student’s question is. Tutors who review essays are told to spend no more than 30 minutes per assignment, no matter how long it is. To do that, several tutors said they copy and paste pre-written feedback.

When tutors miss those targets, managers tell them to speed up. Tutors have been fired for failing to meet their marks, internal records show.

Internally, Paper officials have justified the time limits by saying they allow the company to charge less “so that even underfunded districts (those who need us the most!) can afford us,” Schwim wrote to employees in March, according to a screenshot viewed by Chalkbeat. The company has marketed its tutoring as a way to address inequities among students, “especially those from marginalized groups.”

Several tutors said the breakneck pace makes it harder to help students. One tutor, who left the company in January, said they got a urinary tract infection from skipping bathroom breaks as they tried to keep up with students. Two other tutors said they carried their laptops into the bathroom so they could keep working on the toilet.

“You couldn’t take your hands off the keyboard,” said the tutor who got the UTI, who asked not to be identified because they signed a non-disparagement agreement with Paper, a copy of which Chalkbeat viewed.

Cutler said tutors have told Paper that they take their computers into the bathroom to keep working, but that the company doesn’t “encourage” this practice. Paper recently instituted a “chime” to remind tutors to take their break, he added.

Meanwhile, in Las Vegas, Dickinson figured out a way to get her daughter the math help she needed.

She dipped into her own pocket to pay for private tutoring.

Kalyn Belsha is a national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at [email protected].

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.