A doctoral training centre in wind and marine energy aims to equip PhD students with the skills and knowledge needed to drive continuing expansion in the offshore renewables industry

As the climate crisis intensifies and fuel prices become increasingly volatile, renewable energy sources offer the precious hope of a secure and sustainable future. The sea waters surrounding the UK provide an abundant supply of both wind and marine power, which has driven rapid technical innovation in offshore energy systems as well as the emergence of a thriving industrial sector. As a result the UK is now one of the world’s largest markets for offshore wind, now accounting for up to 12% of the UK’s total energy use, and the country has become a global leader in the development of energy platforms that harness the natural power of the wind, the waves and the tides.

Despite such impressive progress, further expansion in the offshore renewables sector will be crucial for the UK to reach its target of achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. That will require more scientists and engineers to have the skills and knowledge needed to design, build and operate offshore energy platforms that achieve efficient and reliable power generation without damaging the marine environment. Indeed, data collated by the consultancy firm PwC suggests that the number of jobs in the renewable energy sector is growing four times faster than the overall UK employment market, with advertised positions in the green economy almost trebling during 2022.

Developing such specialized skills is the prime motivation behind the UK’s only dedicated doctoral training programme in wind and marine energy. Bringing together leading research groups in offshore engineering at the University of Oxford, marine energy at the University of Edinburgh, and wind energy at the University of Strathclyde, the Centre for Doctoral Training (CDT) in Wind and Marine Energy Systems and Structures aims to equip its students with the technical knowledge and professional skills needed to drive future developments in this fast-growing sector. The four-year programme is supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and part-funded by a number of industrial partners.

According to the CDT’s co-ordinator, Drew Smith at the University of Strathclyde, around 70% of each year’s cohort move directly into the offshore renewables industry, with the remainder staying in the academic sector to pursue research into next-generation offshore energy systems.

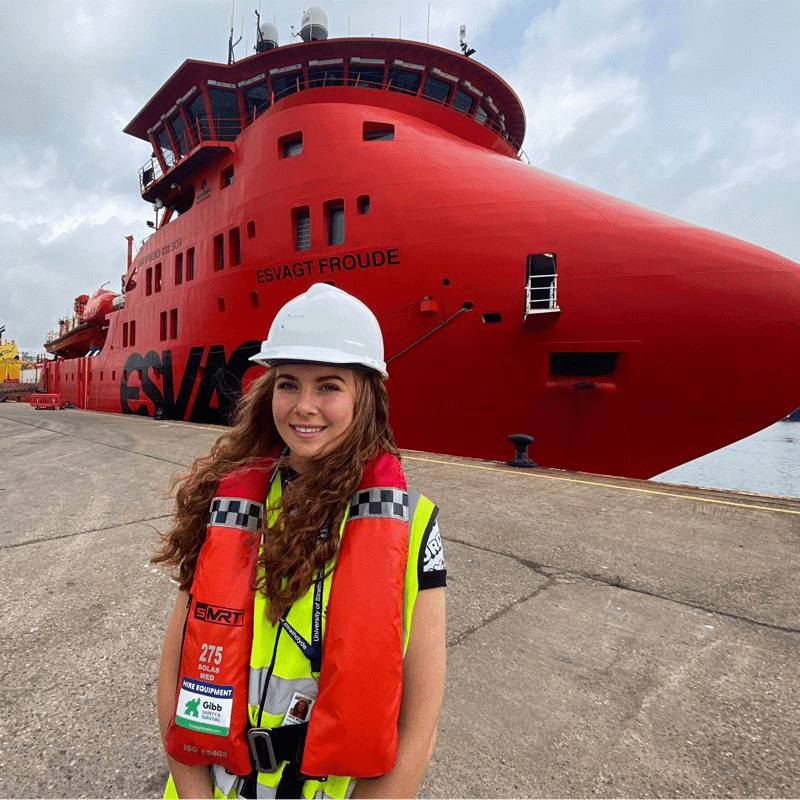

“I knew I wanted to do a PhD, but I was also thinking about my future job options,” says Orla Donnelly, a physics graduate who is now in the second year of the programme. “In my final year I had a module in renewable energy that I really enjoyed, and the CDT seemed like an ideal opportunity for me to start building a career in the offshore energy sector.”

Since most students have very little prior knowledge of renewables technology when they enter the programme, in the first six months all new joiners complete a series of core modules at the University of Strathclyde – with topics ranging from aerodynamics and power conversion through to the safety, risk and reliability of offshore platforms. Students then have the option of taking three further taught modules during their first year, or starting their research project and then choosing another three modules later on in the programme.

Donnelly chose to devote her first year to the formal training, which provided her with a valuable insight into the different technologies involved in building and operating offshore energy systems. “When I started I really didn’t know enough about renewable technologies to know which area I wanted to focus on for my PhD,” she says. “The training year introduced me to the basics of wind, marine and tidal energy, and also allowed me to get to know the academic staff and their different areas of expertise. That made me much more confident about choosing my research project.”

Working through the core modules with students from different science and engineering backgrounds helps newcomers to get to grips with unfamiliar technologies, and to explore the wider economic and environmental factors at play. “We had 18 people in our year, including physicists and mathematicians as well as mechanical, civil and electrical engineers,” comments Donnelly. “We were able to help each other with our specialist knowledge, and that made everything much easier.”

The bonds forged between the students in that first year also generates a strong support network that persists throughout the CDT. “Most people think of a PhD as an individual endeavour, but I have become part of a large cohort of people who are all working in the same area,” continues Donnelly. “Our research projects may be focused on different problems, but we can still offer an opinion if someone runs into an issue.”

Jade McMorland, who is now in her final year of the CDT, has also valued the collaborative nature of the programme. Her research project is focused on the operations and maintenance of next-generation wind turbines, including floating-wind designs that are being developed to enable energy platforms to be built in deeper, and therefore windier, waters. “When I first started there was only one other student who was working on floating wind, but now there are about 10 of us,” she says. “We set up our own research group, which has enabled us to do really fun things like data sprints on real-life operations. If I’ve got a question about something really specific, I know there will be someone in the group who has the specialist expertise to help me.”

McMorland has also been a prime mover in the Professional Engineers Training Scheme (PETS), a student-led initiative that aims to develop skills and competencies that would otherwise be difficult to acquire during a PhD project, such as team management and leadership skills. In large part that is achieved through an outreach programme that includes educational activities at local schools, networking events and seminars, and the organization of the CDT’s annual conference.

The PETS committee also oversees the professional training and skills development needed for students to achieve chartership status, which is a particular advantage for students who are keen to work in industry. “Through PETS and some additional training we try to fulfil all the main competencies needed for chartership,” says McMorland. “Feedback from our sponsored students and our industrial advisory board suggests that it is becoming more important to become a chartered engineer to progress quickly within the offshore renewables industry.”

As well as boosting the students’ career prospects, PETS plays an important role in strengthening the connections between cohorts and the three institutions that make up the CDT. The committee organizes social activities, operates a buddy system to allow newcomers to benefit from the experience of older students, and has a direct link into CDT management to provide a voice for the student community. “PETS was a big selling point for me with the CDT,” says McMorland, who chaired the committee last year and is now co-chair. “It’s nice to have an hour away from your research where you can just chat to other people about all the different activities they’re involved in.”

While many new graduates might be tempted by the immediate career opportunities available in such a buoyant industry, McMorland feels she has benefited from the experience of running her own research project in an environment that has enabled her to make lots of new connections.

“It has been great to explore an area, find a problem that is important to take forward, and delve deep into a topic that I’m really interested in,” she says. “Within a couple of months of starting my PhD I was in Denmark presenting my work, and I’ve really enjoyed the opportunity to engage with different companies in the offshore renewables industry and to attend conferences where other people are really interested in my research.”

• Applications for the CDT in Wind and Marine Energy Systems and Structures are now open for the academic year starting in September 2023. High-calibre candidates should have a first-class or upper second-class degree in mathematics or any scientific or engineering discipline, and must be able to demonstrate excellent maths skills.