In 2017, public interest lawyers sued California because they claimed that too many low-income Black and Hispanic children weren’t learning to read at school. Filed on behalf of families and teachers at three schools with pitiful reading test scores, the suit was an effort to establish a constitutional right to read. However, before the courts resolved that legal question, the litigants settled the case in 2020.

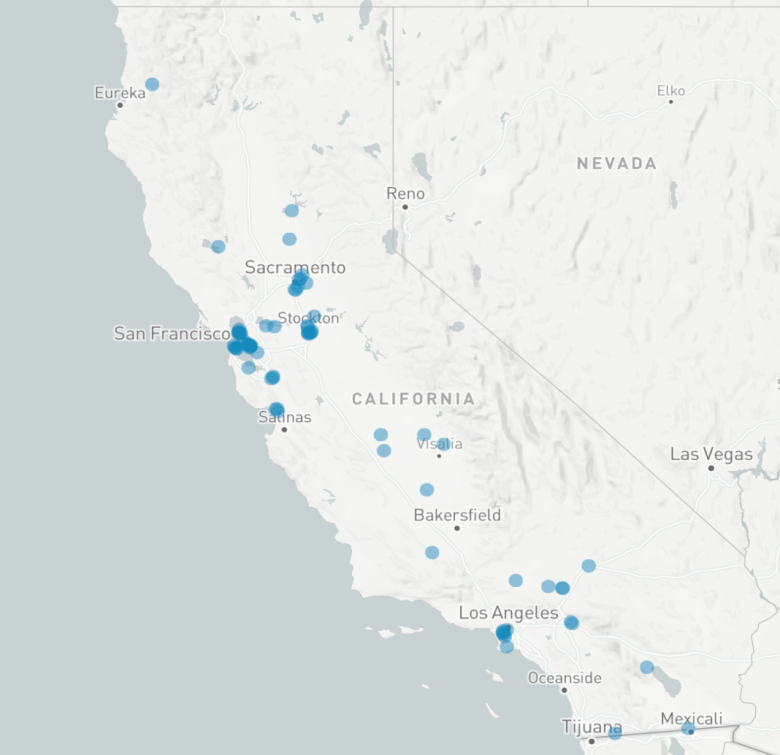

The settlement itself was noteworthy. The state agreed to give an extra $50 million to 75 elementary schools with the worst reading scores in the state to improve how they were teaching reading. Targeted at children who were just learning to read in kindergarten through third grade, the settlement amounted to a little more than $1,000 extra per student. Teachers were trained in evidence-based ways of teaching reading, including an emphasis on phonics and vocabulary. (A few of the 75 original schools didn’t participate or closed down.)

A pair of Stanford University education researchers studied whether the settlement made a difference, and their conclusion was that yes, it did. Third graders’ reading scores in 2022 and 2023 rose relative to their peers at comparable schools that weren’t eligible for the settlement payments. Researchers equated the gains to an extra 25% of a year of learning.

This right-to-read settlement took place during the pandemic when school closures led to learning losses; reading scores had declined sharply statewide and nationwide. However, test scores were strikingly stable at the schools that benefited from the settlement. More than 30% of the third graders at these lowest performing schools continued to reach Level 2 or higher on the California state reading tests, about the same as in 2019. Third grade reading scores slid at comparison schools between 2019 and 2022 and only began to recover in 2023. (Level 2 equates to slightly below grade-level proficiency with “standard nearly met” but is above the lowest Level 1 “standard not met.”) State testing of all students doesn’t begin until third grade and so there was no standard measure for younger kindergarten, first and second graders.

The settlement’s benefits can seem small. The majority of children in these schools still cannot read well. Even with the reading improvements, more than 65% of the students still scored at the lowest of the four levels on the state’s reading test. But their reading gains are meaningful in the context of a real-life classroom experience for more than 7,000 third graders over two years, not merely a laboratory experiment or a small pilot program. The researchers characterized the reading improvements as larger than those seen in 90% of large-scale classroom interventions, according to a 2023 study. They also conducted a cost-benefit analysis and determined that the $50 million literacy program created by the settlement was 13 times more effective than a typical dollar spent at schools.

“I wouldn’t call the results super large. I would call them cost effective,” said Jennifer Jennings, a sociologist at Princeton University who was not involved in the study, but attended a presentation of the research in November.

A working paper, “The Achievement Effects of Scaling Early Literacy Reforms,” was posted to the website of the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University on Dec. 4, 2023. It has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, and may still be revised.

Thomas Dee, an economist at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education who conducted the analysis with doctoral student Sarah Novicoff, says that the reading improvements at the weakest schools in California bolster the evidence for the so-called “science of reading” approach, which has become associated with phonics instruction, but also includes pre-phonics sound awareness, reading fluency, vocabulary building and comprehension skills. Thus far, the best real-world evidence for the science of reading comes from Mississippi, where reading scores dramatically improved after schools changed how they taught reading. But there’s also been a debate over whether the state’s policy to hold weak readers back in third grade has been a bigger driver of the test score gains than the instructional changes.

The structure of the right-to-read settlement offers a possible blueprint for how to bring evidence-based teaching practices into more classrooms, says Stanford’s Dee. School administrators and teachers both received training in the science of reading approach, but then schools were given the freedom to create their own plans and spend their share of the settlement funds as they saw fit within certain guidelines. The Sacramento County Office of Education served as an outside administrator, approving plans and overseeing them.

“How to drive research to inform practice within schools and within classrooms is the central problem we face in education policy,” said Dee. “When I look at this program, it’s an interesting push and pull of how to do that. Schools were encouraged to do their own planning and tailor what they were doing to their own circumstances. But they also had oversight from a state-designated agency that made sure the money was getting where it was supposed to, that they were doing things in a well-conceived way.”

Some schools hired reading coaches to work with teachers on a regular basis. Others hired more aides to tutor children in small groups. Schools generally elected to spend most of the settlement money on salaries for new staff and extra compensation for current teachers to undergo retraining and less on new instructional materials, such as books or curriculums. By contrast, New York City’s current effort to reform reading instruction began with new curriculum requirements and teachers are complaining that they haven’t received the training to make the new curriculum work.

It’s unclear if this combination of retraining and money would be as effective in typical schools. The lowest performing schools that received the money tended to be staffed by many younger, rookie teachers who were still learning their craft. These new teachers may have been more open to adopting a new science of reading approach than veteran teachers who have years of experience teaching another way.

That teacher retraining victory may foretell a short-lived success story for the students in these schools. The reason that there were so many new teachers is because teachers quickly burn out and leave high-poverty schools. The newly trained teachers in the science of reading may soon quit too. There’s a risk that all the investment in better teaching could soon evaporate. I’ll be curious to see their reading scores a few years from now.

This story about the right to read settlement was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.