After years of disappointing, confusing and uneven results, charter schools are generally getting better at educating students. These schools, which are publicly financed but privately run, still have shortcomings and a large subset of them fail students, particularly those with disabilities. But the latest national study from a Stanford University research group calculates that students, on average, learned more at charter schools between the years of 2014 and 2019 than similar students did at their traditional local public schools. The researchers matched charter school students with a “virtual twin”– a composite student who is otherwise similar to the charter school student but attended traditional public schools – and compared academic progress between the two.

“We find that this improvement is because schools are getting better, not because newer, better schools are opening,” said Margaret Raymond, director of Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO), which released its third national charter school study in June 2023. “We see that existing schools are getting better over time and that’s a hugely positive story.”

Hundreds of charter schools were not only outperforming traditional public schools, but had also lifted the achievement of Black and Hispanic students so much that they were learning as much in math and reading as white students and sometimes more, the study found. Racial gaps in learning – a stubborn problem in education – had been eliminated at these charters, which the researchers dubbed “gap busters.” Those findings may provide the best justification for establishing charters, which were intended to be laboratories of experimentation to improve public education.

Starting in the “pits”

The outlook for charter schools didn’t seem nearly this rosy back in 2009, when Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) released its first national charter school study. It was a time of bipartisan support for charter schools and rapid charter school expansion with more than 4,700 charter schools educating over 1.4 million students across 40 states. But CREDO found that the academic results for charter school students were far worse than at traditional public schools.

Raymond, the director of CREDO, recalls the moment in less than scientific terms. “It was the pits,” she said and charter school advocates were “pissed.”

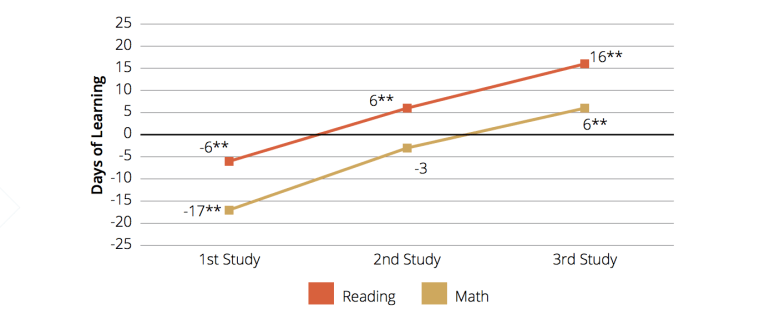

Four years later in 2013, as the number of charter schools swelled to 6,000 students and educated 2.3 million students, there were signs of improvement. CREDO’s second study documented that reading achievement at charters flipped from negative to positive territory. Math scores improved a lot too, but they were still slightly lower than at traditional public schools.

Though trends were heading in a positive direction, it was unclear whether the progress would continue. “In many ways, we’ve been holding our breath for the last 10 years,” said Raymond.

Favored by Black and Hispanic families

According to the latest available data from the 2020-21 school year, there are now 7,800 charters serving 3.7 million students. That’s a big increase, but still a small number compared to the 45 million children who attend traditional public schools.

Disadvantaged children and children of color are more likely to attend charters. Sixty percent of charter school students are poor enough to qualify for free or reduced price lunch. More than a third of charter school students are Hispanic and a quarter are Black, compared with their 26% and 14% shares of the youth population, respectively. Fewer than 30% of charter school students are white.

Black and Hispanic students appear to be doing much better at charter schools, on average, than at traditional public schools. For example, a typical Black student learned the equivalent of 40 more days worth of reading at a charter school in a year, according to the third CREDO study. White students, by contrast, tended to learn no more at charter schools; their annual reading gains were the same at traditional schools and their annual math gains were significantly weaker than at traditional schools.

Despite the academic gains for Black students at charter schools, the achievement gap between Black and white students remains large. A typical Black student student learned two thirds as much in reading as a typical white student did during a school year. In traditional public schools, by comparison, Black students learned only half as much as their white peers in the subject.

Researchers found more than 400 charter schools out of the 6800 they analyzed that managed to avoid these achievement gaps, but they declined to identify them by name. “We have a policy that we don’t name schools because we would then be potentially opening them up to very rapid consequences, both positive and negative,” said Raymond. “We don’t want to be market makers. That’s not our job.”

In the appendix to the report, CREDO identifies the names of charter management organizations (CMOs), charter school chains running multiple schools, that have succeeded in “gap busting.” They include most of the KIPP network schools, Success Academy and the Rocketship schools.

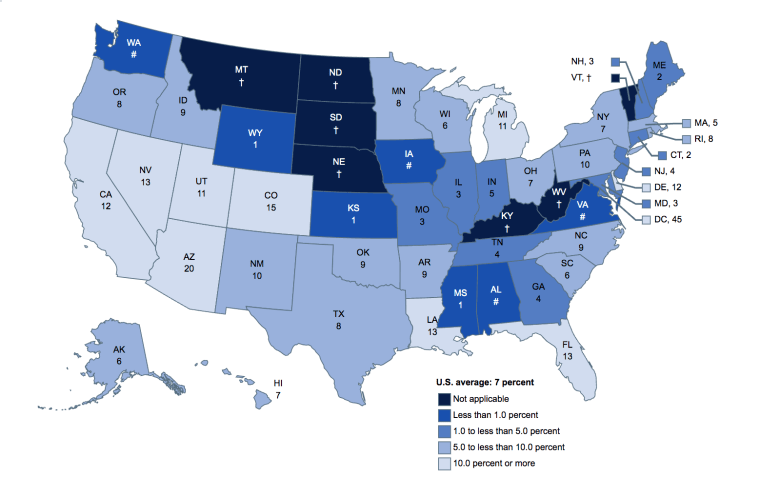

Enrollment in charter schools varies regionally. More than 10% of all public school students attend them in California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada and Colorado. Meanwhile, there are no charter schools in the upper midwest states of Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota.

Charter schools are also primarily an urban phenomenon. More than 85% of charter school students are in cities and suburbs. Less than 15% of charter schools students are in rural areas or small towns. Los Angeles is the U.S. city with the most charter school students with over 150,000. In San Antonio, Texas, charters educate more than half of the city’s students.

No clear advice for schools

On average, students attending charter schools learned the equivalent of an extra 16 days of reading, compared to what similar students learned in 180 days in a traditional public school, and an extra six days in math. Though a few extra days worth of learning may not sound impressive, Raymond noted that this incremental progress bucks the educational stagnation and declines seen in the rest of the nation during these years, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which measures the reading and math levels of fourth and eighth graders across the country and is viewed as a reliable yardstick of academic achievement.

Urban charter schools had the best results with nearly 30 extra days of growth in reading and math, compared to students in traditional public schools. Students in rural charter schools were not doing well in math; they tended to lag behind public school peers by 10 days of learning in this subject.

One frustrating upshot to this body of research is how little concrete advice there is in it for schools. Raymond and her colleagues primarily focused on outcomes and didn’t look under the hood to understand what curriculum and other choices schools are making to get such great results.

“We have investigated whether there’s anything common among the schools that do really, really well and the answer is there isn’t,” said Raymond. “From a policymaker standpoint, that’s sort of a bummer. But it also means that any school can do this. You don’t have to be a particular flavor, or size or shape in order to be successful. There’s lots of pathways to success.”

Some exemplary schools had a “no excuses” strict discipline approach to education. Others had a more lenient culture. Some schools changed their approach during the study period and were able to maintain strong academic performance.

From Raymond’s vantage point, the reason for many charters’ success lies in the combination of flexibility and accountability. Charter schools are freed from many regulations, which allow them, for example, to schedule longer school days and hold classes on weekends. New York City is now requiring elementary schools to choose from three different reading curriculums; charters are exempt. But, unlike traditional public schools, charter schools have to report on student progress every few years – the frequency varies by state and by charter authorizer – in order to renew their charters. The threat of closure looms if results are not good.

“It’s that balance of go out, try new things, build new ideas, test them out, tweak them, tinker, do whatever,” Raymond said. “And know that at some point, you’re going to have to be seriously reviewed for renewal.”

Online charters “devastating” for kids

Still, many charter schools of poor quality continue to operate. The worst results were posted by online charter schools, also known as virtual schools, which enroll six percent of the nation’s 3.7 million charter school students. Students at these schools learned the equivalent of 58 fewer days in reading and 124 fewer days in math than their public school peers. That’s like missing one third of the school year in reading and two thirds of the school year in math.

“The numbers are just really devastating for kids,” said Raymond.

Schools run by charter management organizations [CMOs], the groups that operate multiple schools, generally offered a better education than single, stand-alone charter schools. But a quarter of the CMO schools were still underperforming traditional public schools. “It was a surprise to us that there are still CMOs out there that are replicating even though they’re not doing well by kids,” she said, blaming authorizers for not cracking down on poor performance.

(The report’s appendix also lists CMOs where students aren’t doing well, as measured by student test scores, and they include several well-known charter school chains that have received positive press.)

Backsliding in Washington D.C. and New Orleans

Test scores at some previously strong charter schools declined. The largest decreases in reading and math between the second study in 2013 and the third study in 2023 were documented in Louisiana and Washington, D.C. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, New Orleans converted nearly all of its public schools to charter schools and its early successes were viewed as proof of the charter school concept. That strength has not persisted.

Children with disabilities are another area of “real concern,” Raymond said. They are not getting as good an education at charter schools as they are in traditional schools.

Changes in methodology

Raymond said that the third study covers over 90% of the nation’s charter school students, though it captures only 31 states and the District of Columbia. Some states, such as Alabama, had too few charter schools to make negotiating a data sharing agreement worthwhile. Georgia, which does have a substantial number of charter schools, declined to participate in the third study.

Some criticize the methodology used in the Stanford studies. Critics point out that charter schools cream the best students and counsel out difficult students; it might not be fair to compare charter students to those left behind in the public schools, even if they have similar demographic characteristics and initial test scores. High-achieving children from devoted families who opted for charter schools might have done just as well or better in their neighborhood schools.

The Stanford researchers still stand by their approach, though they have refined how they match student test scores between charter and traditional public schools. In this third study, they refuted the perception that “better” students go to charter schools. They found the opposite in 17 states, where considerably lower achieving students enrolled in charter schools. Those “left behind” in traditional district schools were generally much higher achieving.

Other researchers have taken a different analytical approach, studying lotteries for charter schools that have more applicants than seats available. Presumably all the families who enter the lottery are educationally ambitious and it’s a fairer comparison between those who win and lose seats. In many of these studies, students in charter schools outperform, too.

“Our method comes really, really close to what they find,” said Raymond. “No single study, no triplets of studies are going to be definitive. It takes all of this layering of evidence for a fairly long period of time.”

This story about a national charter school study was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Proof Points and other Hechinger newsletters.