This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

In a classroom on Chicago’s West Side one morning last November, Teresa Przybyslawski sat side by side with a soft-spoken sixth grader. She read a script off her computer screen while he peered at his own tablet.

“On your screen, you will see some addition problems,” read Przybyslawski. “I want you to do as many of them as you can in one minute.”

She glanced at the sixth grader, John. His back was taut, his face tense.

Down the hall, the boy’s classmates at Brunson Math and Science Specialty School, a high-poverty elementary school, geared up to tackle dividing fractions. But here, alongside Przybyslawski, one of the district’s new interventionists tasked with helping students who fell behind during the pandemic, John was about to work on math normally taught in first grade.

“Are you ready? Three. Two. One.”

Numbers flashed on John’s screen: “2 + 7. 5 + 10. 10 + 4.”

At the start of this school year, John, whose real name Chalkbeat is not using to protect his privacy, read at a first grade level and did second grade level math. It would be Przybyslawski’s job to get him caught up – fast.

School districts around the country are pushing to help students bounce back from the pandemic’s profound academic damage: expanding literacy tutoring in Detroit, cutting class sizes in New York City, and buying science-backed reading curriculums in districts across Colorado.

Chicago Public Schools has turned to academic interventionists — a cadre of hundreds mostly classroom teachers already on the district’s payroll, tapped this year to turbocharge the learning of struggling students one-on-one or in small groups.

These newly-minted catchup specialists are tackling three years of COVID fallout layered upon pre-pandemic learning gaps and traumas, at schools that experts and educators agree should have been staffing interventionists all along.

Research has backed Chicago’s intervention approach, and emerging data here and in other cities shows school districts are making headway. But experts say the effort is in its infancy: A recent study by nonprofit test maker NWEA found students are rebounding, but schools are likely a few years away from returning to pre-pandemic achievement, especially for younger learners.

Meanwhile, educators face their own version of Przybyslawski’s countdown.

Three, two, one. Before children like John arrive in high school unprepared, lowering their odds of graduating, starting college or careers, and escaping poverty.

Three, two, one. Before districts like Chicago run out of federal COVID relief dollars.

Three, two, one. Before society at large moves on, and the energy required to remain in full-on recovery mode fades.

As Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, put it at an academic recovery event this past fall: “If we fail to act differently to catch students up, to ensure every student graduates with everything they need, we will have failed this generation and future generations of students.”

One school on Chicago’s West Side tackles academic recovery

Brunson Elementary is in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, one of the hardest hit by COVID and by a surge in the city’s other epidemic: gun violence.

Of Brunson’s 400 students, almost 90% are Black, and almost all are poor. Almost 60% were chronically absent last year, meaning they missed roughly 20 or more days. This year, Brunson has deployed “attendance heroes” — teachers, paraprofessionals, and cafeteria workers — who check in daily with truant students. But across the district, attendance and disruptive behaviors continue to interfere with learning.

“It’s heartbreaking what kids here carry on their backpacks that we can’t see,” principal Carol Wilson said.

Since the pandemic hit in 2020, Chicago Public Schools — like districts across the country — has seen drops in the portion of students meeting reading and math standards on a required state assessment. The district’s latest scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as “the nation’s report card,” showed nearly a decade of growth in math had been wiped out while reading results held fairly steady.

When Chicago schools tested students this past fall to gauge where they stood, two-thirds of John’s sixth grade peers districtwide did not hit grade-level benchmarks in reading. A third were flagged as needing urgent interventions. The picture was similar in math.

Przybyslawski used to teach a classroom of 25 students math and science. Now, her focus is on 15 or so struggling middle schoolers at Brunson.

She set out to create an orderly, efficient operation, using new digital platforms that constantly size up how students are progressing in mastering skills they should have learned in earlier grades — and dictate what they work on next.

In reading, the school piloted an artificial intelligence program that gave students passages to read back to it based on their level and flagged mistakes they made.

She wanted John to divide fractions along with his peers eventually. But in the meantime, Przybyslawski, who also supervises the school’s new team of three tutors, all Brunson grads, measured progress in small increments.

During that session in November, John hesitated briefly before answering 6 + 5.

He was stumped on 3 + 8.

But on the rest, he rattled off the correct answers before Przybyslawski had even finished reading them out.

“We got to the third row,” she told the boy when the minute-long assessment was up. “Very nice work!”

After students left, she logged in their results into Branching Minds, a new platform used for tracking interventions.

Wilson, the principal, and district officials lean on the technology to monitor the progress students are making. Soon, Wilson would also get a second round of standardized tests — administered around the middle of the school year — she hoped would tell her if the school’s efforts were paying off.

‘How can we reach more kids?’

In the bid to speed up students’ academic recovery, Chicago leaders have bet on an arsenal of strategies. They’ve expanded after-school programs, started an in-house tutor corps, and poured millions in teacher training and a new in-house lesson bank called Skyline.

They also tapped some 250 educators to serve as new academic coaches. There are more counselors, social workers, and other support staff.

All in all, the district earmarked $730 million in COVID recovery dollars this school year for its recovery efforts.

Academic interventions — by tutors, classroom teachers, or the new interventionists — are at the heart of the strategy. The district budgeted for at least one interventionist on each of its roughly 500 campuses, though not all schools used the money for such positions, and some schools combined the duties with existing positions. And it required all schools to use the same digital platform to track interventions that Przybyslawski is using.

Across the district this past fall, new interventionists chipped away at catching up tens of thousands of students. One math problem and one sounded-out word at time.

At Moos Elementary on Chicago’s West Side, where most of the 430 primarily Latino students enrolled needed intervention in the fall, Elizabeth Battaglia and the tutors she oversees could reach about 60 students across all grades — not nearly enough.

“How do we get students a lot of extra support with so few people?” she kept asking herself, even as she was encouraged by her students’ growth.

In reading, Battaglia tried a blitz tactic: 20 minutes each day over two weeks when stronger readers are paired with struggling peers to read passages to each other and help correct each other’s mistakes. It helped.

At Sadlowski Elementary on the Southeast Side, where most of the school’s 620 students were flagged as needing intensive help at the start of the year, Emily Gasca has 38 students on her caseload — some of them third and fourth graders reading at kindergarten level.

She enlisted fellow teachers to build interventions into daily classroom instruction, but some colleagues felt she was laying more work on already full plates.

Gasca tried to remind herself she was helping build from scratch a sort of academic safety net that the district has needed all along.

Even before COVID, many Chicago students made it to high school unable to read well. The pandemic just made it harder to look away.

To experts and educators such as Gasca, it’s clear that trauma and social-emotional challenges — that invisible load in students’ backpacks — complicate academic catchup. But struggling to keep up in the classroom is also a daily source of stress, eroding students’ confidence — baggage they carry back home.

Educators search for signs interventions are working

By February, John’s sessions with Przybyslawski were a well-worn routine.

“On your screen you will see a story to read,” Przybyslawski read off her screen to him one morning that month. “I would like you to read this story for me.”

“We’ll begin in three, two, one.”

John looked relaxed in a black face mask, hoodie, and Nikes as he read a passage about a family visit on a farm. At the one-minute mark, a bell dinged, and Przybyslawski smiled broadly. John’s reading had been largely free of mistakes — a huge leap from the start of the school year when he struggled to make it through a sentence or two during those fleeting 60 seconds.

“Good job overall,” she said. “I’ll get your score in a few minutes.”

Przybyslawski’s students were making headway. But now, her caseload looked different.

A few students “graduated.” They still need added help, but should be able to get it in the classroom. A few left the school, part of the customary churn at a high-needs neighborhood campus. And some were no longer on Przybyslawski’s caseload after being identified as needing services for students with disabilities.

Around this same time, Wilson, the principal, had gotten the school’s midyear test results.

Students in all grades were showing solid growth except eighth graders, on that all-important cusp of high school, who were flagged across the district for making little midyear progress.

Wilson was encouraged. Still, these tests predicted that fewer than 10% of Brunson students would meet state standards this spring.

“We’ve seen kids make leaps and bounds but still remain below the benchmarks,” Wilson said. “We’re catching kids up constantly.”

Districtwide in the early grades, there were double-digit increases in students scoring at grade level. Overall, Chicago Public Schools’ scores were in line or better than other urban districts. But much work remained: In the second grade, for example, more than half of students remained one grade level below in math, and a quarter were still two grade levels below in both math and reading.

Paul Zavitkovsky, an expert on testing at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said standardized tests are a helpful snapshot of how students are doing, but he cautioned against relying on them to drive recovery efforts. Remediating one skill at a time based on test results must happen alongside engaging, grade-level instruction — a tough balance to strike, Zavitkovsky said.

Based on an analysis of results on a standardized test named STAR 360 many Chicago elementary schools are giving three times a year, Zavitkovsky found almost all schools made four months of gains in the first four months of the year in math — an encouraging return to a pre-pandemic pace of growth.

But, he said, “Average gains are not going to be enough.”

Dan Goldhaber, who leads the University of Washington’s Center for Education Data & Research, said it’s not clear how long schools can remain in full recovery mode, which requires resources and sustained effort.

When the COVID money runs dry, Chicago’s army of interventionists hired in recent years could land on the budgetary chopping block, leaving classroom teachers to pick up the difficult work of recovery.

Bogdana Chkoumbova, the district’s education chief, says the district is encouraged by testing, grading, and other data; it will cover interventionists at each school and grow the tutor corps next year.

That’s because there’s more work to be done, Chkoumbova recently told the school board. Data show 20% of students have gotten some intervention, and of those, only about a third are on track to meet their goals — an improvement over earlier in the year.

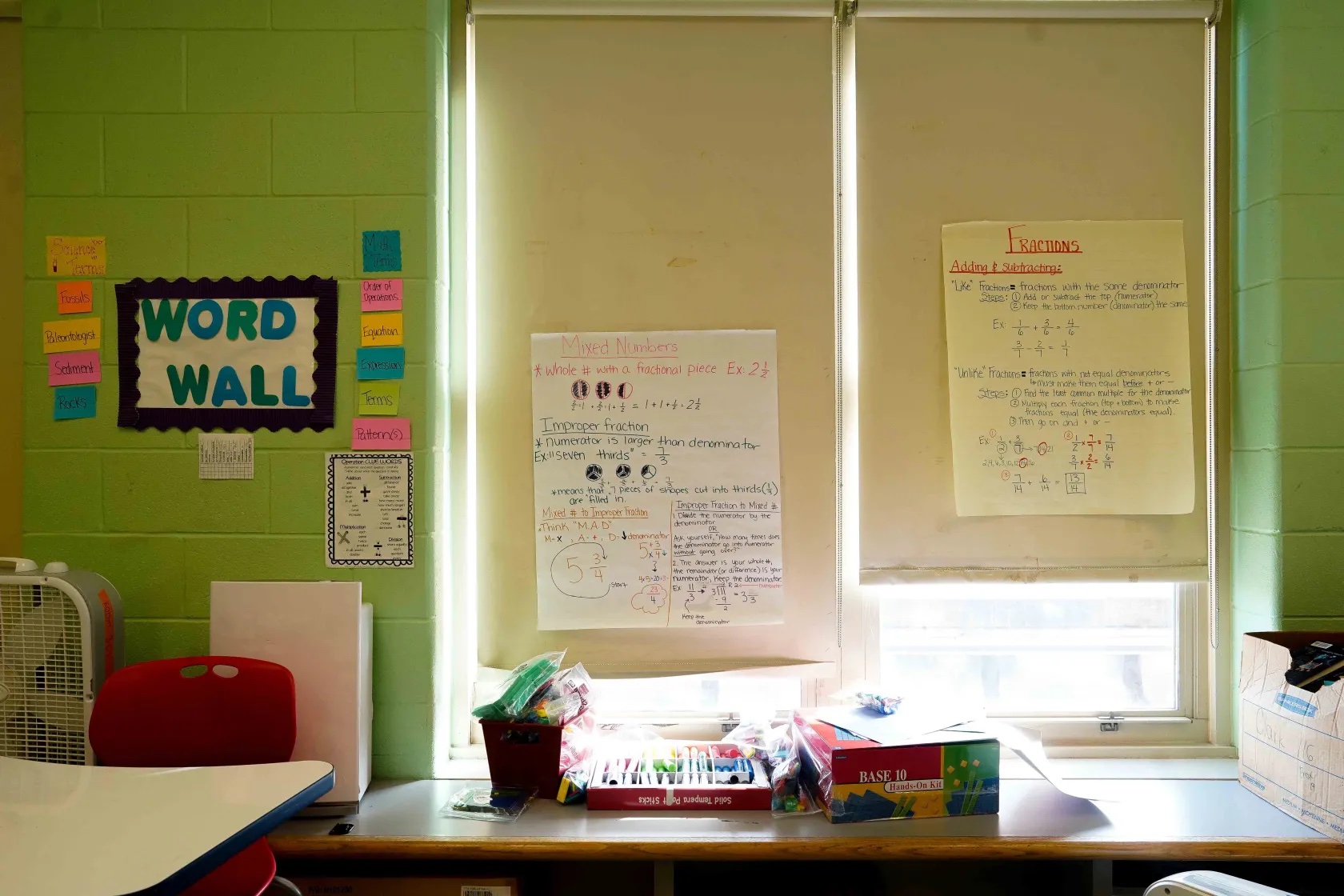

But, as district leaders have noted, a lot of intervention work is not captured by the data. At Brunson, a girl recently asked Przybyslawski for help with multiplication and division off the screens. The interventionist set up stacks of flashcards, quizzing her the old-fashioned way.

“Confidence!” she told the girl. “Just be confident.”

Behind them, in the back of Przybyslawski’s classroom, a bulletin board was covered with certificates of achievement.

One was John’s. It showed a figure looking over a wheat field, a mountain peak rising in the background.

“Congratulations!” the certificate read. “Your reading POWERS are getting stronger, and it’s time to celebrate your hard work.”

Mila Koumpilova is Chalkbeat Chicago’s senior reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Mila at [email protected].

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.