This story about teacher-powered schools was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

BOSTON — Taryn Snyder’s third graders were leaning over their desks, scratching out short essays on what they’d done over the weekend. It was the first lesson in a school week that would take her kids through memoir writing, an introduction to division and research on Indigenous history, each activity carefully curated by Snyder.

But teaching wasn’t the only thing on Snyder’s plate. The next day, she’d meet with other teachers and a counselor to discuss their students’ academic progress and wellbeing. She would also lead an upcoming meeting on the school’s finances, including how to spend federal pandemic relief dollars. And she was running for the school’s governing board.

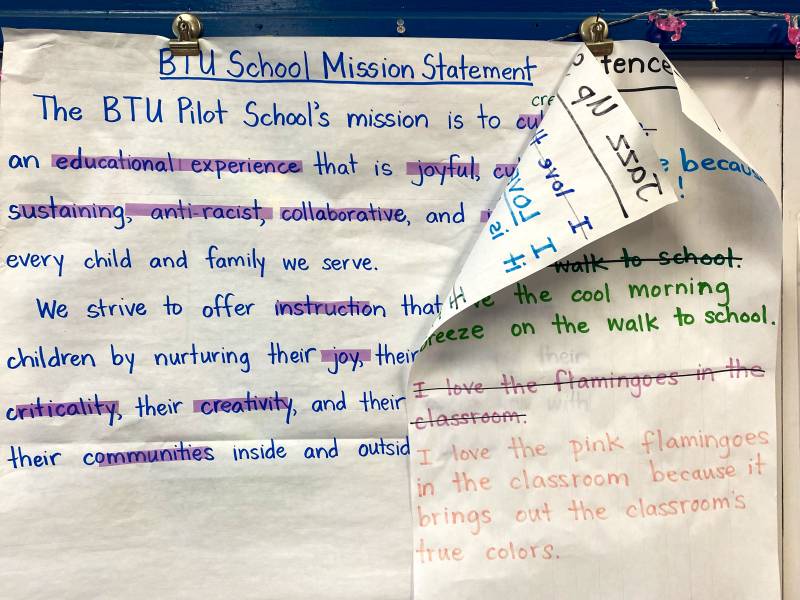

The Boston Teachers Union Pilot School, where Snyder has worked since 2012, is a “teacher-powered” school. The term refers to schools that are collaboratively designed and run by teams of teachers, who have the freedom and authority to make decisions on everything from curriculum to budget and personnel.

The pandemic and travails of remote learning walloped the education profession, worsening teacher morale and contributing to more people exiting the field. At the same time, teachers around the country have watched their autonomy erode, due to such factors as standardized testing mandates, laws governing what can and can’t be taught and growing demands for “parental rights.”

Supporters of the teacher-powered model see it as an important antidote to these trends, as well as to the micromanaging by school districts and administrators that has contributed to more young people shunning the profession. It turns a top-down approach to education on its head, asserting that teachers are most familiar with the needs of students and know best how to help them learn, and that decisions made with little input from teachers can hurt kids and make schools less vibrant, creative places.

Since the pandemic, interest in the teacher-powered model has increased, with schools in a handful of districts taking steps to adopt it for the first time, according to Amy Junge, director of teacher-powered schools at Education Evolving, a Minneapolis nonprofit that supports schools following the model. Some data suggests giving teachers more authority can help with teacher satisfaction and retention: Teachers at teacher-led schools are roughly half as likely to leave their jobs as those at other schools, according to initial findings from a forthcoming analysis of 45 teacher-powered schools conducted by Education Evolving.

“In general, teachers don’t have the kind of voice that other professionals typically do,” said Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. “I’m a former high school teacher, and professors have a lot more say in the decisions that impact their jobs,” he said. “Schools vary, but in schools where teachers have more voice, there is better retention.”

That said, even the model’s most ardent proponents acknowledge that it carries challenges and may not be right for most schools. “Certainly, there are excellent educators who might not thrive in this environment or choose to be in it,” said Junge, citing the extra demands on teachers and their time.

The first schools to take a teacher-led approach emerged in the 1970s at a time of growing interest in the worker cooperative model, in which employees share ownership of an organization, according to Junge. During the 1990s, teacher-led schools began to gain traction in Minnesota, in particular, with the state’s passage of a charter law that allowed teachers to serve as the majority of a school’s governing board. Today, Junge’s group, which coined the term “teacher-powered” in 2014, identifies roughly 300 schools nationwide that follow the model.

The term teacher-powered is loosely defined; schools under its wide umbrella take different approaches. In some cases, schools employ leaders who focus primarily on administration, not teaching, although decision-making still happens collaboratively with teachers. In other cases, teachers lead the school while also juggling teaching loads. At Avalon Charter School, in St. Paul, Minnesota, for example, there are four “program coordinators,” all teachers who still have classroom responsibilities, who take on additional administrative tasks. Carrie Bakken, a social studies teacher and program coordinator who has been with the school since 2001, said the model appeals to younger workers and has helped the school avoid hiring challenges.

“We are really experiencing a teacher shortage here in Minnesota,” said Bakken. But at Avalon, she said, “we are pretty much fully staffed.”

The model at Boston Teachers Union Pilot School, which serves kindergarteners through eighth graders, has evolved since the school’s 2009 founding. The school, located in an aging brick building in the city’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood, was established at the urging of the Boston Teachers Union, hence its name. Today its relationship with the union is limited to having one union official on the school governing board.

Berta Rose Berriz, a bilingual and special education teacher who was hired to run the school as one of its first “co-leads,” said she was drawn to the job because in prior positions she was always finding herself at odds with her principals. They couldn’t understand why she wanted to use books that included images of people like her Spanish-speaking students or why she might pause in the hall to chat with kids. “They didn’t know anything about teaching,” she recalled. “They didn’t get it; they didn’t get what I was doing.”

She and her co-lead, Betsy Drinan, were paid slightly more than other teachers at the school but less than some principals in the district, enabling them to put more money toward instruction, they said. It was important that they be seen not as bosses but as peers. To that end, they taught regular classes — one year Drinan led a seventh grade English Language Arts class, but more often she taught reading intervention. Nearly every decision was reached in collaboration with the school’s entire teaching staff; a single “thumbs down” could kill a proposal.

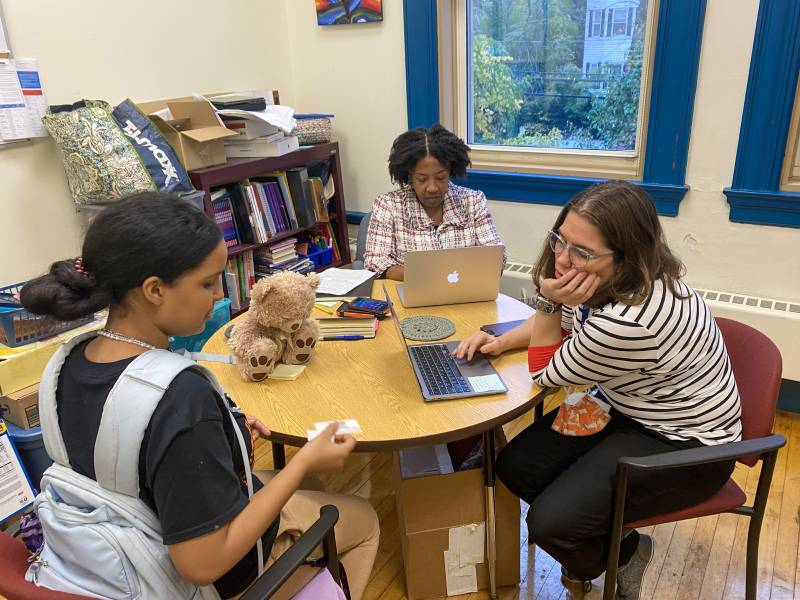

But as those early leaders retired and the school grew, the demands on the co-leads’ time became overwhelming. Then came COVID, and its added administrative burdens. Today, the school is led by Lauren Clarke-Mason and Rebecca Gadd, two educators with classroom experience whose current teaching responsibilities are limited to running clubs, providing instructional support and covering for absent teachers.

The door of their office is marked with a placard that reads “Co-Leads Abyss.” Students often swing by to chat, and the co-leads regularly visit classrooms and coach teachers. Meanwhile, teachers help make decisions about the school’s future in their roles on the different committees — personnel, instructional leadership, scheduling, budget and finance — that meet monthly. The threshold for approving proposals is now 85%, not 100.

“What we really want to do is make teachers’ lives easier,” said Clarke-Mason, who’s worked in Boston Public Schools for 28 years, most recently as an instructional coach. Gadd, a former teacher in New York City’s public schools, said, “It’s not a top-down model. We don’t just decide things and tell teachers they have to go along with it.”

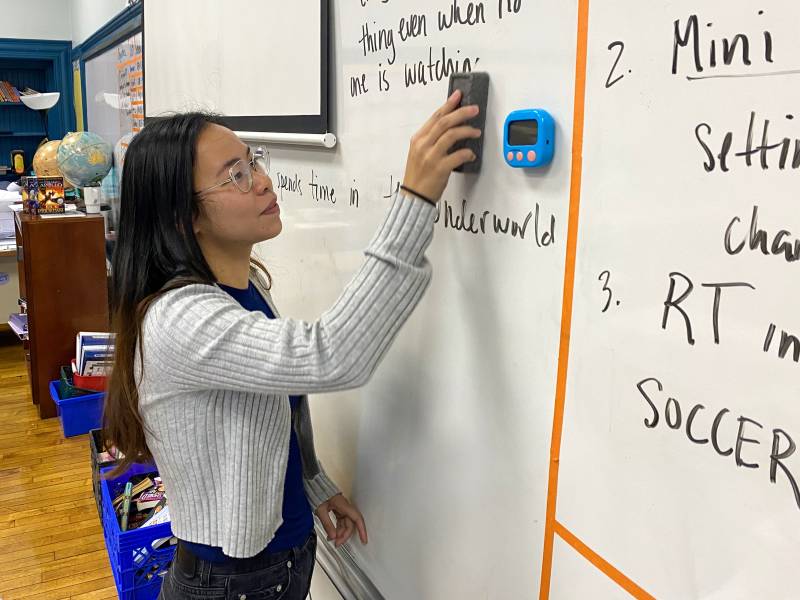

Most teachers in the school’s lower grades have been on staff since its founding. For them, the teacher-led model is what keeps them at the school. But the Boston school hasn’t been immune from teacher turnover. During the pandemic, some teachers in the upper grades left, and this year the school has several new staff members. Phung Ninh is one. A first-year teacher, she joined the Boston Teachers Union Pilot School this fall as an ELA and social studies teacher.

Ninh, a former community organizer who was drawn to the school for its collaborative ethos, said she has flexibility to shape her lessons in ways that other new teachers may not. “Some of my friends at other schools, they’re handed a curriculum and are told, teach this,” she said one day last year during a break between classes. But learning how to teach two subjects, along with participating in so many high-level decisions at the school, is very taxing. “I think this work is more fulfilling in the end,” she said. “But right now, it feels overwhelming.”

Jerry Pisani, one of the elementary school teachers, who has been on staff since the school’s founding, was leading his kindergartners through an art lesson on a Monday. That weekend, a parent had emailed him hoping the class could recognize the Indian holiday of Diwali. Pisani had pulled together a brief lesson, something he said he was able to do in part because the school’s leaders don’t dictate what he teaches and when. That’s not the case everywhere: He recalled visiting another school a few years back where each teacher seemed to be following the same script at exactly the same pace. As he moved from one classroom to the next, teachers delivered practically the same sentences at the same time, he said.

Some students notice that their school is unusual. “It feels different not having a principal,” said Ella, a fifth grader with long blond hair who’d transferred to Boston Teachers Union Pilot School three years earlier. “At the school I was at before this, ‘principal’ is a word teachers would use, not to threaten you, but to make you listen to them,” she said, noting that a principal served primarily as an authority figure rather than someone who had relationships with students. “Having co-leads is just much better.”

In Snyder’s class, third grader Wyatt declared the school “pretty amazing.”

“If something is going on, the teachers can also make a decision about that, and I like that much better than just one person deciding,” said Wyatt, who spoke from behind a gray mask.

Wyatt’s mother, Abby Coakley, was at the after-school pickup one soggy afternoon last fall. She had worked in Boston Public Schools as a dance teacher for seven years, until she burned out and decided to train as a nurse. When it came time to send her own kids to school, she thought the teacher-led model might offer something very different from her own experience — and she was right.

“It seems like the teachers here really want to be here,” said Coakley. “All the teachers seem really, really devoted to the kids.”

Junge’s group is advocating to have at least one teacher-powered school in every district, to give more kids and educators an option. Just as doctors can choose to work for a large health system or start their own small practice, teachers ought to have a choice of working environment, said Lars Edsal, executive director of Education Evolving.

In addition to the school-wide model, there are lighter-touch ways of embracing a teacher-powered philosophy, educators said. Teachers can be given more authority over instruction and more input on some school decisions while the school retains a more traditional administrative structure.

Since the pandemic, Education Evolving has been hearing from more school districts that are losing teachers and want to explore the teacher-led approach as a possible solution, Junge said. Maricopa County, in Arizona, plans to introduce the model at six schools this fall, while two Washington, D.C., charter schools are also adopting it, according to Junge.

But while school culture is important, it can’t alter some of the structural issues driving people from the profession, such as low pay. Last year, teachers earned just 76.5 cents for each dollar earned by similar college graduates in other professions, and the median earnings for elementary and middle school teachers has declined by more than 8% since 2010.

“We do absolutely attract more teachers,” said Avalon Charter School’s Bakken, a fact she attributes to the teacher-led model. “But as someone who is looking at our pay and then at the housing costs in Minnesota, I’m terrified. I don’t know how you ask a teacher to make $43,000 and the rent is $1,600.”

But Snyder, in Boston, can’t imagine being anywhere else. She worked in advertising after college, then went back to school for education and ended up as a student teacher at Boston Teachers Union School. She said she loves being able to adapt her curriculum each year to the needs of her students.

Her classroom is decorated with pink flamingos — plush, fluorescent and blowup versions. She works all the time, but loves vacation, and the flamingos are one attempt to bring a holiday vibe to the classroom.

“It is a lot more work. We all put in countless extra hours,” said Snyder. “But I think for all of us, it’s worth it because we feel a certain level of investment. And we build a school around the belief that teachers are the ones who should be making decisions.”

This story about teacher-powered schools was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.