Where have all the bookworms gone? Recreational reading has been shown to reduce stress and improve working memory, but fewer children are reading for fun than ever before. In recent surveys by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, 16% of 9-year-olds said they never or hardly ever read for fun, compared to 11% in 2012 and 9% in 1984. Among 13-year-olds, that number was 29% in 2020, compared with 22% in 2012 and 8% in 1984.

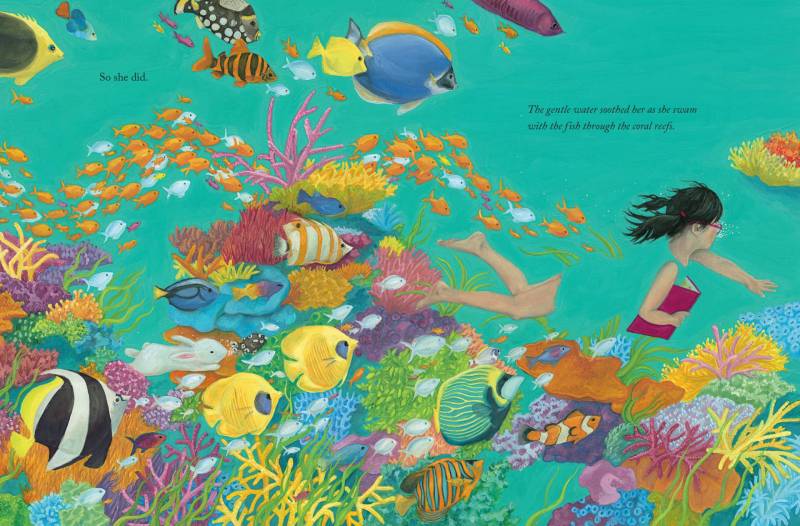

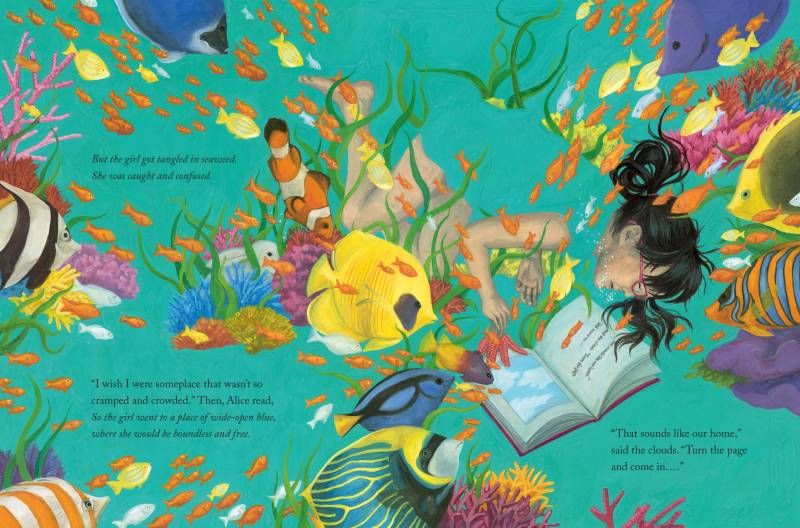

Authors Grace Lin and Kate Messner believe books give readers the ability to experience new worlds and empathize with others. Together they wrote “Once Upon A Book,” a children’s picture book where the main character Alice is swept away on an adventure through the magic of reading.

“There is a perfect book for everyone,” said Lin. “You just have to find it.” However, there is an art to matching kids with the right book. For parents and teachers who want children to cultivate a love of reading, Messner and Lin provided tips on how to help kids find wonder through books.

Let kids pick their own books

Adults sometimes seek out award-winning children’s books only to find that their kid has no interest in reading them. As a parent, Lin had to reconsider her lofty expectations. “[My daughter] wanted her ‘My Little Pony’ book and she wanted Curious George stories – not even the original Curious George books, but the cheap, knock off Curious George books,” said Lin. “Letting go of this idea that I needed her to read ‘good books’ is what I think really has made her love and enjoy reading.”

When kids have room to gravitate to the books that spark their interest, it helps them cultivate their identities as readers. Letting kids choose their own books leads to more motivation to read and ownership over the reading process, whereas imposing a book on a child can make the child feel like reading is a chore instead of a treat. “What makes a great book is just the simple fact that a child loves it,” said Lin. “The fact that they’re reading is great.”

Just because a kid rebuffs esteemed literature, it doesn’t mean those books should be thrown out or given away. Messner recommends putting them in kids’ vicinity. When her son only wanted to read Tonka truck books from the grocery store, she still kept other books around the house.

“They were always on the bookshelf and in the baskets and on the table and by the bed and all over the place,” said Messner. “When you live immersed in words like that, you eventually find your way to the other stories. And I think that’s a really powerful way to introduce kids to ideas.”

Give everyone access to windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors

As an author/illustrator known for bringing her Taiwanese heritage to her work, one of Lin’s biggest fears is that after Lunar New Year, students won’t read another book with an Asian character until the following year. When teachers only bring books about different cultures into the classroom during holidays, they’re participating in cultural tourism, Lin said. “It’s like Asians only exist during the Lunar New Year and Black people only exist in February.” She invites teachers to make sure that diverse books surround children every single day of the year.

Lin encourages teachers and parents to see books as windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors, a framework developed by scholar Rudine Sims Bishop. Books that are windows show readers new worlds, mirrors show readers themselves, and sliding glass doors allow readers to fully immerse themselves in a story. “Books as mirrors are very important because that is what gives a child a sense of self-worth,” Lin said. “It tells them that they can be the hero in a book. They can be a changemaker. They are the ones who have control in their world. And that’s something that a lot of people from marginalized groups have not had for a long time.”

She advises teachers and parents to be tactful about how they make books as mirrors available to children of color. “My mother tried to get me to read Asian books. I wouldn’t touch them because I just didn’t want to be reminded of how different I was from my classmates,” she said. Educators and parents can make it clear that kids of any identity can and should explore diverse books. “Push the book with the Black character onto the Asian child. Push the book with the Asian character onto the white child,” she said.

Recommend books in stacks

What Kate Messner misses most about her 15 years as a middle school English teacher is putting the perfect book into a reader’s eager hands. If a teacher has a book they think will benefit a student, she encourages them to recommend a stack of books rather than one book at a time.

“Instead of saying, ‘This book has an Asian character and you’re Asian, so you should read this book,’ which is awkward and uncomfortable, what we can do is say, ‘Oh, here are four books I think you might love,’” Messner explained. The four books might actually focus on another topic the student is interested in and feature at least one Asian character. “Recommending books in stacks is a really great way to introduce kids to stories, but also let them feel the ownership of choice.”

Stacks are particularly helpful when students are going through something difficult and a teacher wants to give them a book that helps them through a tough time. “I would have kids who I knew were dealing with various tough situations outside of the classroom. Maybe I knew they were struggling with a relative with addiction or maybe I knew that they had some history that was difficult,” Messner said. With these students she’d find and suggest a few books where the main characters overcame a variety of challenges.

“I’d just present the stack to them and then go away, so that kid who might really need that one book can choose it themselves without me standing over their shoulder,” she said.

Books have the power to spark children’s interest, broaden their understanding, reflect their experiences and affirm their identities. Every time young readers feel empowered to choose a book for themselves is an opportunity to create a lasting relationship with reading.